Arts Commentary: On Michel Houellebecq, Islamophobia, and “Charlie Hebdo”

It is unlikely that those who turned automatic fire on the staff of Charlie Hebdo ever read Michel Houellebecq.

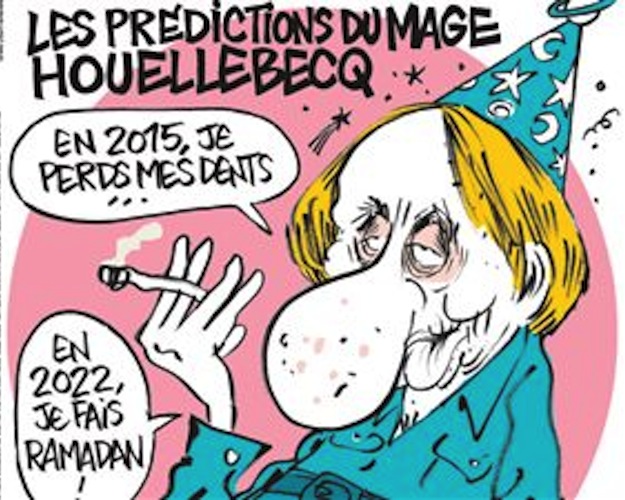

The cover of the latest issue of “Charlie Hebdo.”

By Harvey Blume

Novelist Michel Houellebecq is pictured on the cover of the recent, fateful issue of the French satirical publication Charlie Hebdo as absurdly bulbous and sodden. He wears a sorcerer’s pointy cap decorated by images of Saturn, stars, and phases of the moon, beneath a headline in a typeface that might be termed *ivre* — or drunken, were there such a typeface, announcing the predictions for 2015 of Houellebecq the mage. It is predicted that in 2015 he, Houellebecq, will lose his teeth, not that he looks to have any in the crumpled jaw portrayed in this cartoon, and, further, that in 2022 he will celebrate Ramadan.

The caricature is more anti-Houellebecq than anything else but not necessarily more anti-Houellebecq than he himself aspires to be in his novels. Houellebecq is a man of many dislikes, a writer who perfects a distinctively French sourness. It is unlikely that those who turned automatic fire on the staff of Charlie Hebdo ever read Houellebecq. Then again, how many of those enthused by the fatwa against Salman Rushdie ever thought it necessary to actually read The Satanic Verses? In some quarters exposure to the written word remains fraught and subversive.

This is not to deny Houellebecq’s Islamophobia, hardly. It is only to situate it. In his 2003 novel Platform Houellebecq excoriates Islam, much as he does Judaism and Christianity. He is a serial excoriater; his whole talent is to be disappointed and to excoriate. He could also, as in the following review, be termed a serial misanthrope. Throughout his work, Houellebecq never finds a lack of things to dislike about our species.

Above all, Houellebecq’s a stimulating writer. I am tempted to compare him to Don DeLillo in his intellectual range, except of course DeLillo continues to entertain higher hopes.

Here is my review of Houellebecq’s novel Platform, a book that is new atheist, or perhaps, anti-theist, before either of these terms had entered common parlance.

Platform, translated by Frank Wynne, Knopf, 2003.

While touring for his latest book, Platform, French novelist Michel Houellebecq called Islam “the stupidest religion” and derided the Koran as second-rate scripture. Several Muslim groups thought these views amounted to “Islamophobia,” and sued Houellebecq for inciting racial hatred. In October, 2002, a panel of Parisian magistrates cleared Houellebecq of all charges. (A month later, another French court refused to dignify similar charges against Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci with so much as a verdict; with true bureaucratic panache, judges threw the case out on grounds of errors in the legal paperwork).

If writers couldn’t take cracks at religion, it would severely crimp their style, and throw some out of work entirely. Gore Vidal, for example, has made a career out of savaging the Judeo-Christian tradition. And Norman Mailer, in other respects Vidal’s rival, thought the Gospels such a shambles that he vowed to give a better account of the Christ story with his novel, The Gospel According to the Son. Houellebecq resembles Vidal more than Mailer. He will never be moved to rewrite the Koran in the hope of improving it. And though critics have managed to overlook the fact, Platform‘s attack on Islam is part of a sweeping indictment of all monotheist faiths, starting with Judaism.

This critique is voiced by an Egyptian who pulls Michel Renault, the book’s main character, aside on his trip to the Nile’s Valley of the Kings, to make fun of the Sinai and the burning bush where Moses famously “flipped his lid.” Michel usually reacts to people with a sneer or a sigh, but this “intelligent and often funny” Egyptian gets his attention. The man proceeds to inform Michel that: “The closer a religion comes to monotheism . . . the more cruel and inhuman it becomes.” Catholicism, in his view, escaped the absolute “mindlessness” of Islam because it allowed for the “the cult of the Virgin and the Saints,” and fostered the “ingenious invention of the angels.” Absent such polytheistic elements, monotheism devolves toward barbarism. Islam’s famed “mathematicians, poets, and scientists,” according to this Muslim, who is the book’s real Islamaphobe, must have lost their faith in order to achieve what they did.

Passionate as this passage may be, it would be a mistake to take it as a sign that Platform is a concerted tirade against religion. The book is too unfocused for that, religion being only one many things that disappoint or irritate Michel. Nor does the writing strive to reach the boiling point of real tirade. Michel is frequently annoyed, but rarely outraged. Numbness is his best defense. He is in the grand tradition of French anomie; his unhappiness eludes diagnosis. It is not a result [of] bad parenting, bad wiring or poverty. It is not explicable in terms of psychology, neurology or sociology. It just is. In fact, in an age when just about everything is deemed to have a cause and, therefore, at least in principle, a cure, Houellebecq’s insistence on the sheer durability of Michel’s malaise may be his novel’s most significant achievement.

Still, when it comes to griping, Michel doesn’t have to strain to come up with particulars; the book, in large measure, is a extended litany of them. Michel, for example, is averse to American novelists (John Grisham, for one), allergic to Western women (with one notable exception), and turned off by contemporary art (typified by an installation in which flies, bred in an artist’s excrement, are released into a gallery). He is petulant about global warming, which has resulted in inedible fish breeding in French rivers, and genuinely pained about the effects of globalization. As he sees it, globalization has allowed sourpuss westerners like him, every one of whom “reeks of selfishness, masochism, and death,” to foist their awful social system on the rest of the world. In the logic of Platform, Islamic terrorism has a special role to play; it is world’s coarse, murderous way of saying thanks but no thanks to globalization.

Author Michel Houellebecq — his antipathies extend well beyond religion.

Michel works in the Ministry of Culture, which makes him privy to the ways of artists, most of whom, he finds, are like entrepreneurs who, “carefully reconnoitered emerging markets, then tried to get in fast.” Valerie, his lover, works for a tourist agency, and their inexhaustible passion for each other is seen as a nearly miraculous exception to the extinction of sexual desire that is the rule between western men and women. As Michel puts it: “Something is definitely happening that’s making westerners stop sleeping with each other.” With regard to sex, most westerners past the age of thirty are condemned to “suffering permanent withdrawal.”

But not Michel. He will not settle for the usual substitutes — pornography or S&M, which, he says, could only flourish “among overcultured, cerebral people for whom sex has lost all attraction.” Inert or aloof in most contexts, Michel’s enjoyment of sex — or, in his words, his abiding “enthusiasm for pussy” — is one of his “few remaining recognizable, fully human qualities.” And so he does what it seems to him most Europeans do whenever they get the chance, namely, flee the continent for more hospitable sexual climes. It is, in fact, Michel’s special affinity for Thai prostitutes that brings him to the Thailand beach resort where he meets Valerie. When they rendez-vous back in Paris, he suggests that her flagging travel agency make sexual tourism its chief selling point, and she agrees immediately, convincing her boss to implement the plan.

Michel and Valerie are happy together. She is the one woman in his experience who is at least the equal of a Thai prostitute in her capacity both to give and to receive pleasure. And sex tourism puts Valerie’s agency ahead of the competition, without Michel or Valerie incurring any guilt as a result. Michel believes global market forces have brought unprecedented ruin to countries like Thailand. Why, then, he asks, shouldn’t such countries be able to take exonomic advantage of their resource of sexual expertise?

Then comes a deadly Islamic terror attack, leaving Michel, once again, alone, and without even a hope that the miracle of Valerie will be repeated in his life.

Platform came out in France before 9/11 but 9/11 apparently did not dissuade French Muslim groups from suing Houellebecq for slander. Religionists, not only monotheists, are funny that way, quick to take insult, even in the face of facts. In any case, Houellebecq’s antipathies extend well beyond religion. In his previous novel, The Elementary Particles, he blamed the generation of 1968 — sometimes known in France as the “soixante-retards” — for his country’s ills. Houellebecq is a serial misanthrope, moving from one nemesis to another. Though his animosities never rouse him to the kind of fiery invective for which Celine, to whom he should otherwise be compared, was noted, Houellebecq is a good enough writer to make you wonder who or what will offend him next.

Harvey Blume is an author — Ota Benga: The Pygmy At The Zoo — who has published essays, reviews, and interviews widely, in The New York Times, Boston Globe, Agni, The American Prospect, and The Forward, among other venues. His blog in progress, which will archive that material and be a platform for new, is here. He contributes regularly to The Arts Fuse and wants to help it continue to grow into a critical voice to be reckoned with.

Is Michel the novel’s protagonist Michel the writer? Could you explore that a bit?

>Is Michel the novel’s protagonist Michel the writer? Could you explore that a bit?

Yes, that’s him.

What I find interesting is the transition from Houellebecq the Islamophobe to Houellebecq, a la Submission, the new novel — from what I have read about it (it’s not yet in English) — to Houellebecq the Islamophile — from Houellebecq who despises monotheism of all sorts in Platform, to Houellebecq who requires & submits to the strongest form of it he can discern.

How very French. Did not Rimbaud flee his dissipation and enervation in a search for stronger races?

Houellebecq gives up his dissipation and enervation in a search for God.

Allah will do.

OK, I admit, I’ve never read Houellebecq, who lately has been coming at me from all sides, including a rave from J. Hoberman in Bookforum. So, Harvey, help people ignorant as I am. Which books of his should we read, and in which order? And why?

Gerry,

I’d read The Elementary Particles in which he takes it out on the generation of ’68 — the soixante-retards — of whom I am one. Some of my peers — the likes of Paul Berman, for example, fuss, fume & fulminate in umbrage — but I, soixante-retard that I am, enjoy.

I’d read Platform for the reasons I hope I’ve spelled out well in the above review. That may be his best or at least most relevant novel.

Then, if I had room for more, I’d read The Map and the Territory (2012), in which he is in exile from France.

Why read him?

Literary rubbernecking of course. But beyond that, I, for one, admire his deep global irritability and disillusionment. Silly, huh? He’s interested in ideas, even bad ones. He has a roving mind and probably a pov that only a European, no, a French writer, can bring to bear.

And now, given his wavering between Islamophobia and something very like its opposite, I have begun to think of him of as a writer who puts the need for religious faith into a fresh context. If he were writing about whether or not to go to church, who would care?

That’s an answer! Thanks.