Visual Arts Commentary: Alex Katz — Superficiality Equals Profundity?

Through July 29th, the MFA in Boston is presenting “Alex Katz Prints.” Time to take a look at Arts Fuse Critic Franklin Einspruch’s thoughts on the artist, posted about an exhibition of Katz’s paintings at the Farnsworth Art Museum, Rockland, Maine.

Alex Katz. Sharon and Vivien, 2009 Oil on linen 84 x 144 inches ©Alex Katz/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Alex Katz: New Work. Farnsworth Art Museum, Rockland, Maine, through October 31, 2010

By Franklin Einspruch

I learned to hate the banal scenarios and lazy pop culture references of Ann Beattie in an English class in college, and it didn’t surprise me to learn some time ago that she had penned the introduction to a 1990 monograph of the work of Alex Katz. Katz, whose 2008–2009 paintings are the subject of an exhibition at the Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland, Maine, exemplifies a cultural phenomenon of deliberately superficial treatments. Andy Warhol is a common ancestor.

As with Warhol and Beattie, the argument on behalf of Katz’s work posits that the apotheosis of superficiality results in profundity. The glib presentation of pretty faces is said to honor the crassness of the larger culture or perhaps lampoon it or maybe both at the same time. The featherweight psychological treatment supposedly provides cover for an insightful project. When Katz claims that nothing is more mysterious than appearances, as he did in a recorded 2005 conversation with Robert Storr, he is ostensibly saying something akin to Giorgio Morandi’s assertion that nothing is more abstract than reality.

Or maybe he is not, and beneath the surface lies an icy substrate of cynicism. A friend of mine whose eye I respect rather likes Katz, and we argued about this in front of his works in the exhibition “Painting Summer in New England” at the Peabody Essex Museum in 2006. My friend thought the lightness was joyful; I thought the cool paint application made his long tableaux look like cheap carpets. I went to Rockland hoping to settle the matter.

Katz typically works 10 feet wide, and a background hum of Abstract Expressionism accompanies his paintings despite their operation in a cool, knowing Pop universe. In the catalog, a charming 30-page affair with a complete set of color plates of included works, independent curator Mark Rosenthal likens the portraiture to Warhol and Chuck Close, but it frequently happens with Katz that the better paintings function as abstractions. There are some good pictures made out of bad parts. His portraiture is stilted in full-face, awkward in three-quarter, and laughable in profile, in which facial anatomy wriggles away from him like an eel.

Alex Katz, Homage to Monet 7, 2009 Oil on linen 72 x 144 inches ©Alex Katz/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

But his color sense is canny, particularly given his favorite palette of orange, blue, and black, and he knows how to distribute forms across the big canvasses so that they compose. The result, sometimes, is an effective painting despite the fact that the five-foot-high heads that make it up are a little ridiculous. Often the background, an arbitrary but well-chosen color painted flat from one end to the other, saves them by providing a mighty unifying element. It is portraiture conceived upon the template of a Barnett Newman “zip” painting.

Abstraction does not always come to his aid though. He laid in a drippy, blue sky behind his triple portrait of David Ross, Robert Storr, and Irving Sandler. This painting calls out for two urgent corrections. The first is to fix Sandler’s collar and lapels so he doesn’t look like a disheveled grandpa and Katz doesn’t look like he has misunderstood how a jacket fits a man’s shoulders. The second is to clean up the mess that ensued when Katz added clouds to the background using a brush loaded with turpentine. They release paint from the sky in neat rows of raindrops that fall upon the trio of art world poobahs. Sandler, the venerable historian of Abstract Expressionism, seems unamused by the affectations of postwar, nonobjective painting that are wetting his scalp as he looks blankly at the viewer.

With all due respect to Ross, Storr, and Sandler, Katz’s one-shot technique functions more effectively when he has a pretty girl to work with. I hesitate to call this out as a failing because it’s true to some degree for the whole post-Medieval history of European art and its American continuations. But it bears upon the question of whether these paintings are apparently or essentially superficial. Pretty girls can be alluring even with no interior life, and I think it’s no accident that better figurative Katzes come to pass when the subject has nothing to contribute except her comeliness and tasteful choice of dress.

Complexity, psychology, and surface variation defy Katz’s artistic predilections, so he dials them down to zero, allowing him to paint the big, flat shapes that he’s good at painting. They are emotionally vacuous, truly and to the core, and this is forgivable not because of what it might say about the culture at large or its Warholian coolness, but because it tends to drive the paintings toward a satisfactory visual conclusion. Depth of any kind would be a needless hurdle.

Satisfactory, I should say, with the exception that the paintings end up as documents of a certain kind of access to the attentions of powerful art world figures, the company of slender, stylish women, and other trappings of that echelon of society. This is no crime in itself, but it doesn’t provide much frisson, and it leads to wondering whether even Katz’s landscapes celebrate a similar access to the beautiful vistas of Maine.

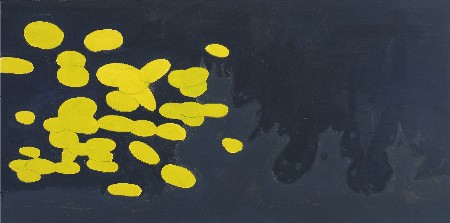

Alex Katz, Homage to Monet 5, 2009 Oil on linen 72 x 144 inches ©Alex Katz/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

These at least are less problematic. As a former Skowhegan student and part-time Lincolnville resident since 1954, he has had a long time to admire those views, and his renderings of them better justify their outsized scale and flat treatment. Freed of figures, and thus the burden of comparison to greater achievements in portraiture and figure painting, the landscapes can be decorative without being uncompensating. Better still, Katz plays with them more inventively. The best works in the exhibition are his views of water lilies on the surface of a pond. (Have no fear, he entitled all of them “Homage to Monet”). Katz duly lifted the horizon line above the picture and studied the reflections, but instead of Monet’s flickering, we get Katz’s swaths, and they are striking. “Homage to Monet 5” is especially fine, with a black apparition of foliage floating on slate-gray water, undercutting the cheerful, yellow lily pads that confine themselves to the left side of the painting as if reluctant to venture further.

“Reflection 5” works on similar principles, depicting shadows of trees and a dusk sky evocatively reflected in water. Two paintings of the sunset through silhouetted pines are not so hard-hitting at first save that one of them is 16 feet wide, but they reveal grandeur on prolonged inspection. (Again, there’s that palette of orange, blue, and black.) Regarding the show as a whole, it’s as if the psychology walked out of the portraits and crept into the landscapes. Perhaps it would be a worthy project for this senior and undiminished artist to make the figures follow it there.

Franklin Einspruch is a Boston-based artist and writer. His website is einspruch.com; follow him on Twitter @franklin_e.

Tagged: Alex Katz, Alex Katz: Prints, Andy-Warhol, Farnesworth Art Museum, Franklin Einspruch, Maine, MFA, Painting

How refreshing to read such an honest, straightforward, this-is-how-I-see-it review!

Nice review and I’m glad to see images of the work since it’s unlikely that I’ll get up to Maine. Interesting especially to see the homage a Monet after seeing the real panels at MOMA this weekend. The comparison speaks to your critique.

BTW, I’m a New Yorker who grew up going to MOMA, and I hadn’t been there for a couple of seasons because I hated the renovation. For anybody waffling about going to the megaplex it’s become, I’d urge them on. Seeing just the Monet after all these years was a revelation—not to speak of spending time with some of the rest of that enormous and wondrous collection.

Katz is an easy target, scarcely worth shooting at, and, more to the point, scarcely worth looking at. He is chiefly remarkable as an example of how far insubstantial style can go when it hits a certain chord with a certain moneyed or influential crowd. This is nothing new except that in the past, more was required in terms of technical prowess, and Katz is rather thin and anemic in that department.

He obviously has an audience and a market (which need mean very little in terms of actual merit), presumably made up of people such as those he portrays. It is, of course, inconceivable that he could be taken seriously as portraitist by anyone with tolerable knowledge of the genre, certainly before 1960. As for the landscapes “after” Monet, at least the ones pictured in this review, they must be dramatically diminished by reproduction, for they appear quite inconsequential, not to say banal.

I still remember seeing a small Katz at an Art Basel, which was so utterly dull and undistinguished, even for him, that I asked the price out of perverse curiosity. It was in the low five figures, as I recall, but my point is that I wouldn’t have wanted the thing as a gift.

So, in closing, very nice review, but it reads like good art writing in search of a better subject.

[…] sell tons and tons of it,” he said, noting that the striking cover — an Alex Katz painting of two young women staring at presumptive readers — has also played a part in its popularity. […]