Book Review: “Outside Music, Inside Voices” — Illuminating Conversations about Creating Jazz

Jazz fans with open ears should rush to this book: so should anyone interested in the creative process, its rewards as well as its challenges.

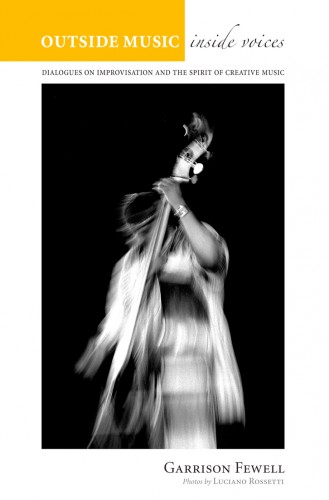

Outside Music, Inside Voices: Dialogues on Improvisation and the Spirit of Creative Music by Garrison Fewell. Photographs by Luciano Rossetti. Saturn University Press. 329 pages. $25. Also available as e-book at iTunes, Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Smashwords.

By Michael Ullman

Guitarist Garrison Fewell’s beautifully titled Outside Music, Inside Voices is a series of interviews or dialogues with 25 musicians engaged in what we used to call free or avant-garde jazz, but which Fewell labels “creative improvised music.” It’s an exploration of the thoughts of others, and at the same time an introspective investigation of his own path. As trumpeter Baikida Carroll says in his interview, “Music helps me make meaningful connections within myself.” Fully improvised music is about self-exploration, and also about encounters with the spirits and capabilities of others in real time: the engagement in the book’s dialogues seems a natural extension of the sharing and openness in the music.

Guitarist Garrison Fewell’s beautifully titled Outside Music, Inside Voices is a series of interviews or dialogues with 25 musicians engaged in what we used to call free or avant-garde jazz, but which Fewell labels “creative improvised music.” It’s an exploration of the thoughts of others, and at the same time an introspective investigation of his own path. As trumpeter Baikida Carroll says in his interview, “Music helps me make meaningful connections within myself.” Fully improvised music is about self-exploration, and also about encounters with the spirits and capabilities of others in real time: the engagement in the book’s dialogues seems a natural extension of the sharing and openness in the music.

In his dialogues with acknowledged giants in this field, such as Wadada Leo Smith, Baikida Carroll, Henry Threadgill, Milford Graves, Marilyn Crispell, Oliver Lake, and with lesser known, but nonetheless important, figures, Fewell is sensitive, probing, and finally bold. He wants his subjects to talk about what Threadgill calls their “spiritual intent.” As Fewell puts it, “The motivation for this book comes from my experience as a jazz musician turned creative free improviser and my desire to illuminate the metaphysical or spiritual aspects of creative improvised music.”

Shedding light on the transcendent quality of music sounds more intimidating than it turns out to be. The quest comes naturally out of Fewell’s experience as a musician. He summarizes his path in the preface: “When I was young and had not yet learned the “right” notes to play, improvisation was natural and joyful, and playing an instrument represented a passageway into the universe of sound where I experienced something of the eternal in my daily life. Later, when I went to school to study jazz, improvisation became more of a technique for applying the correct scales to chord changes.” Fewell went on to become an accomplished, even celebrated, bop or hard bop guitarist.

But after 20 years something changed in Fewell and he moved to free jazz: “It was not a conscious decision to adopt a new musical style, but an evolution—a change of heart about the way I heard music and the way I wanted to express myself. I haven’t abandoned my affection for straight-ahead jazz, but I find in creative improvised music and the players I work with the kind of freedom of expression and excitement that originally attracted me to music.” It was a perilous step, and it lost him some of his more traditional fans.

The satisfactions of the process of group improvisation made up for the career difficulties. Fewell insists that:

At a certain moment, even in the midst of chaos, a ‘sound unity’ will occur—you can hear it happen—where individual and collective exploration converge and the music becomes connected to a greater energy. The vibrations in the room become more intense, the overtones more pronounced. It’s a physical as well as emotional energy that unifies body and mind. When it’s over, everyone in the room knows something happened. But what? The question remains to be answered by the performers and audience, but from a player’s point of view, I can say that it never happens the same way or in the same place twice.

There’s remarkable unanimity about what it takes for something like a ‘sound unity’ to happen. It calls for decades of practice and plenty of guts. The late soprano saxophonist Steve Lacy, a brilliant philosopher as well as musician, talks about improvisation as taking a leap. You need an appetite for it, “because unless you do, you’re really not alive. If you’re not secure enough to take the plunge, then you’re really in trouble, and you’d better go back and practice until you are secure enough to drop the security.” Others talk about letting the music taking control of their conscious minds, and even of having the music coming through them. Lacy says it well: “If the music is good enough, you’re not thinking. You’re not just hearing it, taking part in it.” At best, according to the great bassist Joëlle Léandre, “When we play, and definitely when we improvise, we become the other one. This is the reality when we improvise because everything is open. We are at the same time a performer, improviser, and composer of vibration.”

Bassist Joëlle Léandre. Photo: Luciano Rossetti.

In his interview, Fewell’s mentor and frequent collaborator, the late John Tchicai, explains it this way: “Someone’s playing you, and you are listening.” For the audience, according to pianist Matthew Shipp, there are various possible experiences: “Music is a meditational point for some people; for some people it’s just an exercise to listen, or they listen to it, they intellectually get something out of it, or don’t get anything out of it. For other people, it touches them at a very deep level, and then it can change you. But that’s dependent on your openness to be changed. The music has that potential, but when somebody listens, it depends on their intent and their openness for those things to happen.”

In these interviews one learns fascinating details about certain musicians’ lives: composer Nicole Mitchell’s first memories of playing music were on the street in San Diego, “making animated improvisations to characterize each person that walked by”; Roy Campbell identified the keys of the gospel music his mother played on the radio by color; when he was a baby, bassist Henry Grimes reached up to the piano in his home, pressed some keys, and thought “this meant that I had invented music.” For some, these discoveries were lifesavers. Ahmed Abdullah told Fewell, “When I bought my first trumpet at the age of thirteen from money I earned sweeping the hallways of the apartment building next to where my family lived, I didn’t know I was embarking on a life of spiritual evolution. I was just trying to deal with the pain that I didn’t know how to verbally express, and felt most comfortable attempting to develop a new voice to express myself. That voice was going to be the trumpet, but I didn’t know that when I purchased the instrument.” Marilyn Crispell was 28 when she heard John Coltrane’s “Love Supreme”: “Suddenly there was this presence in the room and—not to get very New Agey here or anything, but I definitely felt this presence and it was an overwhelming feeling of love, pure love. I was crying and totally, totally shaken up, and I asked this presence for help to become part of all of this.”

Henry Threadgill. Photo by Luciano Rossetti.

In the volume the players and composers are remarkably articulate and thoughtful about what they are doing and about the reasons they are doing it. They point us in interesting directions, often by reminding us of key figures that have been overlooked: saxophonist Marion Brown was an “earthquake.” The book is enlightening about the creative process as well as about experiences in the lives of key musicians. There are also some surprising revelations: I was amused by Irène Schweizer’s way of distinguishing the avant-garde music scenes in different countries. The Dutch are humorous, the Germans powerful, the English “fine and open.”

The book comes with biographical sketches of the interviewees and contains magnificent black-and-white photographs by Italian photographer Luciano Rossetti. Jazz fans with open ears should rush to this book: so should anyone interested in the creative process, its rewards as well as its challenges. Brilliantly, Outside Music, Inside Voices ends with a combination warning and invitation from master saxophonist and composer Threadgill: “See, that’s the thing about music—it won’t allow you to decode and breach it on a literal, spoken level. You do your best with words, but then there’s just a place where you can go no further. You’re using words and stuff to talk about something else, another world. There’s a limit to that. As a matter of fact, you have to be careful; you can start to do a disservice if you’re not careful. How many times have you walked into a gallery of paintings and somebody is telling you so much about a painting on the wall and you say, ‘Wait a minute, hold it! The painting speaks too, past anything you say with words, and if you keep talking like this, you’re gonna confuse me and set me off on another track about this painting.’”

Threadgill concludes that “talk will not give you anything in the way of being touched by the power of a work of art . . . the final thing that will convince you is you entering into it for yourself and seeing what happens.”

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for The Atlantic Monthly, The New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, The Boston Phoenix, The Boston Globe and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

Tagged: avant-garde jazz, Baikida Carroll, free jazz, Garrison Fewell, Henry Threadgill, Marilyn Crispell, Milford Graves, Oliver Lake, Outside Music Inside Voices