Film Review: “Stolen” Beauty

A gorgeous documentary examines the 1990 heist of priceless art from Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.

By Betsy Sherman

It must be hard to decide at what point to undertake a documentary about an ongoing investigation. What if events conspire to make the film you’ve shot seem half-baked, or even irrelevant? Rebecca Dreyfus’ “Stolen,” about the 1990 heist of 13 priceless artworks at Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, transcends this problem by weaving into the true-crime saga a rich character study that links together three figures from different time periods. Moreover, “Stolen” is an exceptionally gorgeous documentary, with polished visuals and pithy editing. Sadly, the spaces at the Gardner Museum where Vermeer, Rembrandt and Degas works (among others) once hung remain empty. Even a five million dollar reward has not loosened the tongues of anyone who knows who the two thieves were (the men entered the small museum during the wee hours of March 18, 1990, posing as policemen) or where the paintings and other pieces are now.

The stars of “Stolen” are the museum’s founder, Isabella Stewart Gardner (1860-1924), Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675), and septuagenarian fine arts detective Harold Smith (who died in 2005). The first two are visionaries who saw beyond the conventions of their time. Gardner is described as the first American art collector and the first woman to design and build an art institution (correspondence between Gardner and her agent in Europe, Bernard Berenson, is read in voice-over by actors Blythe Danner and Campbell Scott). Vermeer’s insightful artistry is prized all the more because only 35 of his paintings survive (this includes the Gardner’s “The Concert”). Smith was a brilliant investigator whose efforts to recover stolen artworks benefited the common good.

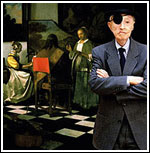

“Stolen” encourages the viewer to look beneath surfaces. The first invitation is presented in the person of Smith himself. Stricken with severe skin cancer, the detective wears an eye-patch, has bandages on his ravaged skin, and has a prominent, reconstructed nose. Beneath the patchwork surface is a warm-hearted gentleman (and dapper dresser) who becomes our guide through the seedy world of art thieves and informers.

“What a world the dealers’ is, and what a lamb am I,” laments the aesthete Berenson in a 1909 letter. He describes those from whom he procures masterpieces for Mrs. Gardner as “the most distressingly odious people in the world.” Smith is no lamb, but he’s clearly a superior being to the mugs with whom he keeps company while tracking down stolen property.

In the film, we’re introduced to the missing Gardner works when reproductions of them are held by Smith’s readily identifiable, mottle-skinned hands. Dreyfus gives much screen time to an analysis of Vermeer’s “The Concert,” in which a pianist accompanies a woman singer (and Vermeer depicts himself, but facing away from the viewer). One scholar explains how a painting-within-the-painting, depicting a bordello transaction, makes for a contrast between low life and high life — just as Dreyfus examines the worlds of commerce and culture in her film.

As part of his investigation, Smith sets up a phone line at which people can leave messages related to the heist. The detective hopes that a disgruntled ex-wife or cohort, enticed by the reward, will spill the beans about the perpetrators. Snatches of these voices, including some crackpot ramblings, are played over restless montages.

Television reporter Ron Gollobin expounds on Boston’s underworld, and Boston Herald reporter Tom Mashberg tells of his exploits chasing down a promising lead on one of the Rembrandts in 1997 (the case “tore a year out of my life”). Smith has on-camera meetings with a couple of locals who, if not directly involved, may have valuable information: Myles Connor (who once walked out of Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts carrying a Rembrandt) and William Youngworth. The film communicates Smith’s skepticism about Youngworth by showing the latter’s image on a monitor and having Smith switch it off dismissively.

There’s a prowling feel to the camerawork in “Stolen” (which was shot by cinema verite veteran Albert Maysles). At one point, we rudely peer into the Gardner crypt, nearly repeating the thieves’ violation of the homey little museum. Scenes that show off Boston, recently and a century ago, are complemented by scenes of the city with which Gardner was obsessed, Venice (she rebuilt a Venetian palazzo within the museum walls).

Dreyfus waits until an hour into the movie to bring up James “Whitey” Bulger, the fugitive Boston-Irish mob superstar. Even if Whitey wasn’t involved in the robbery, says Gollobin, he would have heard about it within two seconds and would have gotten a taste of the profits.

To follow up on leads that point to Ireland, Smith jets to London and meets with a colleague, Dick Ellis of Scotland Yard, and with Paul “Turbocharger” Hendry. This colorful loose cannon is a reformed art thief who now describes himself as a facilitator, helping to return purloined artworks to their owners. “Turbo” has a plan to get the Gardner masterpieces back, which involves Ted Kennedy, an Irish politician who’s an ex-IRA man, and the depositing of the artwork in a church confessional.

The film conveys a hint of Smith’s exhaustion at hitting dead ends, but emphasizes his enthusiasm. “When I recover a painting,” he says, “I’m walking on air.” There’s actually a lot of love in “Stolen.” The Vermeer scholars praise the master and his masterpiece with tearful reverence. Gardner’s passion for giving a world-class collection a home in Boston is palpable (“Let us aim awfully high,” she tells Berenson). One memorable interviewee, gallery attendant Frank DiMarco, bubbles over with affection for “Belle” Gardner — and makes a startling personal revelation.

The opening close-up of Mrs. Gardner’s eyes in John Singer Sargent’s famous portrait, the paint now cracked with age, is echoed in the final close-up of Smith, his damaged face partially hidden by the eye-patch and bowler hat. A century collapses, and suddenly a dogged sleuth becomes a chivalrous knight.

After seeing this film many years ago I became fascinated by the Gardner Heist. I have since viewed more about the heist but nothing matches Stolen.