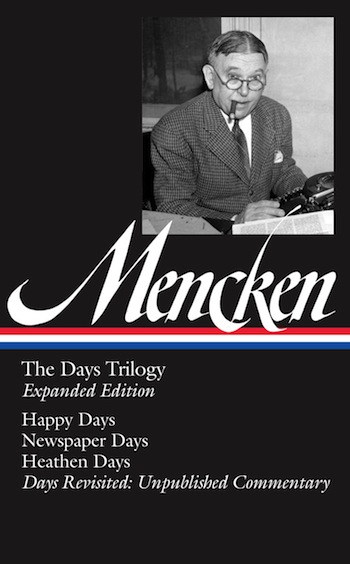

Book Interview: Marion Elizabeth Rodgers on the Expanded “Days” of H. L. Mencken

In The Days Trilogy, Expanded Edition, H. L. Mencken comes off as a marvelously mellowed master, his trademark savagery smoothed over, its energy focused on generating a pungently picturesque vision of a vanished America.

By Bill Marx

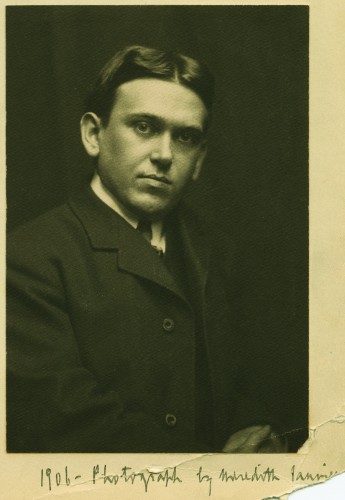

In the mid-1930s, approaching “the perhaps indelicate age of sixty,” famed journalist H. L. Mencken was in the mood to look backwards rather than forwards. After the death of his wife Sara, he returned to his childhood home in Baltimore and promptly embarked on a re-creating his past in what turned out to be three thoroughly delightful books whose nostalgic warmth and comic panache rejuvenated his sagging popularity, which had dipped considerably since his days as a notorious gadfly stinging “Boobus Americanus” in his bestselling Prejudices volumes of the 1920s, a fadeout no doubt encouraged by his disdain for Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the New Deal.

In Happy Days (1880-1892) (1940), Newspaper Days (1899-1906) (1941), and Heathen Days (1890-1936) (1943) Mencken comes off as a marvelously mellowed master, his trademark savagery smoothed over, its energy focused on generating a pungently picturesque vision of the streets, sights, sounds, and routines of a vanished America. The books jump from Mencken’s idyllic childhood eating hard crabs from the Chesapeake Bay (they are “at least eight inches in length …and with snow-white meat almost as firm as soap”) to his days as a reporter covering the great Baltimore fire and observing the demise of the colossi of drink (“My actual belief is that Americans reached the peak of their alcoholic puissance in the closing years of the last century”). There are also his vivid memories of covering the Scopes trial: “The atheist who suffered in the town calaboose was a traveling showman who wandered in with his chimpanzee to make propaganda for Darwin.”

It turns out that the Days volumes have been incomplete. Mencken continued to annotate and add new reflections on the published volumes with the stipulation that these pages not be made public until twenty-five years after his death. More than 200 pages of this material is contained (as “Notes”) in the Library of America’s The Days Trilogy, Expanded Edition (872 pages, $35), edited by Marion Elizabeth Rodgers, who also served as the editor of LOA’s two-volume set of Mencken’s Prejudices series. (Arts Fuse interview).

After reading through the additional prose in the “Notes,” my feeling is that when they are not gossipy, drily factual, or stiffly polemical the material complicates our picture of Mencken’s past — there are glimpses here and there of sore spots the writer steered clear of in the published volumes (especially Mencken’s air-brushed picture of his carefree youth). The overall impression left by these exhilarating volumes is that Mencken, challenged to come up with his remembrance of things past (“Something is surely missing … The Americano no longer dances gorgeously with arms and legs”) responded with nothing less than transcendent brio. His memories may not be Proustian (or Freudian) but they are still an enormous amount of fun. I e-mailed editor (and Mencken biographer) Rodgers some questions about the accuracy of The Days Trilogy, the peculiar nature of Mencken’s reminisces (there is scarce personal detail to be found,) and the value of these books today.

Arts Fuse: LOA calls The Days Trilogy a classic American autobiography. Yet in these volumes H. L Mencken mentions little about himself (he omits his wife completely as well as the banning of his magazine American Mercury in Boston) and there is next to nothing about his intellectual development. He focuses on the world around him, mainly the turn-of-the-century. How would you characterize these books?

Marion Elizabeth Rodgers: As the teacher/writer William Zinsser explains so well, a memoir isn’t the summary of a life: “it’s a window into a life, very much like a photograph in its selective composition.” That is how I would characterize the Days books. During the troubled 1930’s and early 40s, as the world hurtled towards war, Mencken would often turn his mind’s eye to his youth and reflect on those long lost days of childhood. Here are the light-hearted accounts of Mencken’s introduction to music and his genesis as a bookworm, character sketches of his family and the men and women who lived in the alley behind his home, the routine of Americans from an earlier time. The Days books were Mencken’s valentine to the past, a record of an earlier era, as he put it, “now fast fading into the shadows of forgotten history.” As he said to the poet Edgar Lee Masters, “We were passing through Utopia, and didn’t know it.”

When Mencken’s publisher, Alfred Knopf, reprinted the trilogy in 1947, the difference between his past and present struck home with particular poignancy. “We were lucky to have been born so soon,” he wrote. “…I enjoyed myself immensely, and all I try to do here is to convey some of my joy to the nobility and gentry of this once and great and happy Republic, now only a dismal burlesque of its former self.” I often think of that marvelous line when I reflect on life today. Now, if your readers are searching for less nostalgia, and yearn for an autobiographical record of Mencken’s intellectual development, then I advise they turn to Thirty-Five Years of Newspaper Work (edited by Fred Hobson, Vincent Fitzpatrick, Bradford Jacobs, 1994) and My Life as Author and Editor (edited by Jonathan Yardley, 1993). But they will be missing a vital essence of Mencken by ignoring this expanded LOA edition.

AF: In what ways do the “Notes” add to our appreciation of The Days Trilogy? Mencken mentions his wife, but only glancingly, while there is meticulous documentation of people (servants, coroners) and places in the text. Is there something in the “Notes” that is of particular value to you, a Mencken biographer?

Rodgers: Seen by only a few Mencken scholars, the “Notes” are important primary material filling in personal and historical gaps in Mencken’s biography. They contain private reflections missing from his Diary or any of his other autobiographical narratives or correspondence (including those mentioned above). When published in conjunction with The Days Trilogy, we see the difference between Mencken the man and the public persona, making this work all the richer. He recollects the personalities involved in the 1917 revolution in Cuba, as well those of the Scopes Trial. He demonstrates his empathy for the downtrodden of his city and his admiration for the Zionist settlers he met in 1936. Of interest are Mencken’s entries on contemporaries from the political and theatrical world, including William Jennings Bryan, Al Smith, Richard Mansfield and William Fawcett. We are given intimate details of his childhood and family, and the revelation of prejudices harbored his parents, grandparents and other relatives. There is an emphasis on daily life and popular culture in the United States, especially before both World Wars. You get a vivid sense of the individuality and lack of standardization that existed among people and daily life during that period; a deeper understanding of the German-American culture in Baltimore that helps explain Mencken’s bitterness when it was wiped out after World War I.

AF: How accurate is The Days Trilogy? Mencken admitted to some skeptics that he sometimes went ‘for the good story” rather than the bald facts.

Rodgers: The stories are mainly true, but, as Mencken admitted, with “occasional stretchers.” To Mencken what mattered, as he cited Charles Lamb, was “a fair construction, as to an after-dinner conversation.” For those who yearn for absolute accuracy, we have the “Notes” that accompany this volume; Mencken took great pains to verify names and dates for the record. When it came time for me to write my biography, Mencken: The American Iconoclast (Oxford, 2005) I added more correctives to the canon: the more truthful account of how he applied for his first job during the blizzard of 1899, two weeks after his father’s death; and the bifurcation between fact and falsehood in his dispatches of the Battle of Tsushima in the Russo-Japanese War of 1905.

AF: Would it be fair to say that the latter part of Menken’s career was dedicated to preserving the past, his version of Stephen Zweig’s The World of Yesterday? He worked on Thirty-five Years of Newspaper Work and My Life as Author and Editor after completing The Days Trilogy. Also, how conscious was his effort to create a “kinder, gentler” Mencken? These books revived his popularity.

Rodgers: The Days books were actually the inspiration behind those wonderfully rich volumes. Mencken said he had found that his recollection, when put to the test, ”often turned out to be inaccurate, and sometimes grossly so.” So then he divided his life into two parts: his life as a newspaperman, and the other his career as the author of books and as a magazine editor. He was well aware that his files of papers, manuscripts, memoirs and correspondence would serve as an important and interesting record of the history of American journalism during his time, and even a general history of the country, and provide “entertainment for dozens of nascent Ph.D’s in the years to come.” As for his consciously creating, as you say, “a kinder, gentler Mencken,” no, no, this was not deliberate nor was it a mask that he put on! Local readers of Mencken’s column in the Baltimore Evening Sun knew this sentimental side of him long before the Days books were published: how he could wax eloquently about “The Age of Horses,” “Spring in These Parts,” “On Living in Baltimore.”

AF: One critic wrote that Mencken’s style in these volumes has reached its apex. The writing is always “robust and exuberant,” but balanced to the point of “almost classical perfection.” Do you agree? What do you see as the strengths of his prose?

Rodgers: In Mencken’s early writing we get a sense that he is deliberately trying to shock or show off; in the later work, as we find in the Days books, or in the accompanying “Notes” to these volumes, there is a genuine command of language and ease of style. He was the man who searched for the perfect word, so that when you are reading him, there is, as he put it, ”the constant joy of sudden discovery, of happy accident.” On display is his humor, his common sense, a glittering vocabulary that sends readers scurrying to the dictionary.

I will give you just one example from this expanded LOA edition. It is contained in his notes to “Drill for a Rookie” (Newspaper Days). The essay describes his first assignments as a young reporter when he accompanied the police on their rounds. One evening he was with them on their investigation of the suicide of a teenage girl, who, according to Mencken, had trusted a young man a bit too much. Mencken recalled that she looked almost angelic, lying dead on the parlor floor. If she had lived, Mencken wrote, “she’d be a grandmother, with her conscience long since worn to a stump, and her old age lighted by sentimental memories of her first love affair.” That phrase — “conscience long since worn to a stump” — don’t you just love that? So simple, yet so vivid. There is nothing banal or clumsy about it! Mencken was never one to fall back on a store of stale clichés; instead he was always devising the unexpected. One of the characteristics of Mencken’s prose is its clarity and confidence.

AF: Could you talk about The Days Trilogy in terms of the response of contemporary sensibilities to Mencken’s stark libertarianism and his references to blacks, Jews, etc —

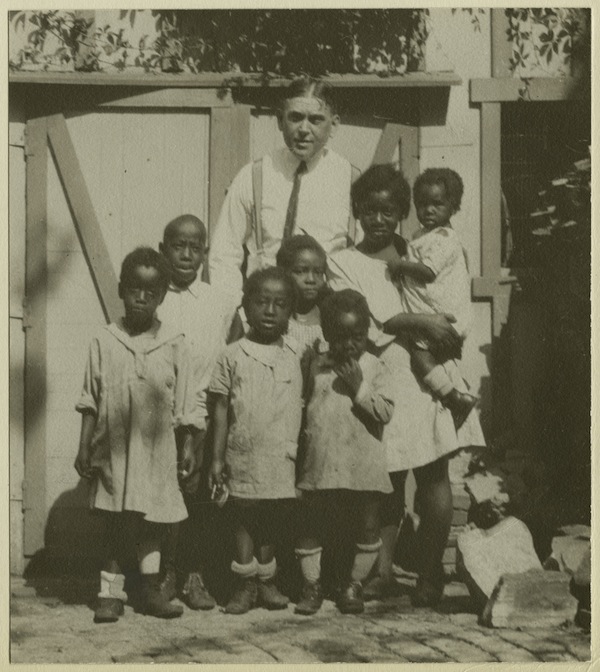

Rodgers: The Days books are as much about race relations and cultural beliefs from 1880-1936 as they are about Henry Louis Mencken. Mencken grew up in Baltimore, with strict barriers placed between whites and African-Americans, between classes of society, between Gentiles and Jews (and, until the horrors of the second World War brought them together, between the German-Jews and those from Eastern Europe). Understanding that is key in understanding Mencken. So the Days books puts Mencken in the context of his time and place. Here was a boy who listened to the Coon songs then popular at the time, who spoke the colloquialisms then current.

And yet, and yet! Out of this heritage, from this particular family during this time and place in American society, Mencken counteracted and broke barriers when he published the work of W.E. B. Du Bois and George Schuyler in his magazines; wrote against lynching and segregation; when he celebrated Yiddish plays, examined the immigrant press, encouraged the writing (and befriended) persons ranging from U.S. Senators to hobos. We get a glimpse of how this writer, raised to become a cigar-maker like his father, evolved into what Walter Lippmann called “the most powerful personal influence on this whole generation of American people.” In Mencken’s attempt to draw serious and meaningful conclusions about his life, the man who emerges in this LOA edition is not the vague legendary figure but the actual Baltimorean, with flaws and imperfections as well as genius on display.

AF: Do you have a favorite chapter or story in the volumes? One of my picks would be the comic saga of the preternaturally intelligent Frank the pony [“Memoirs of a Stable”] in Heathen Days.

Rodgers: Absolutely, “Memoirs of a Stable” ranks in my top five! Whenever I show students the Mencken House in Baltimore (on 1524 Hollins Street, now closed, alas) they always get a great kick out of seeing the actual dining room window where Frank would mischievously poke his head through so the Mencken family could feed him ice cream. Modern audiences find it incredible to believe that a Shetland pony once lived outside in the yard, but if they look at Mencken’s description of “Baltimore in the Eighties” (in Happy Days) they will get a vivid flavor of what life was like in America during those golden years. I also love “Inquisition” with Mencken’s memories of the Scopes Monkey Trial of 1925, and “Romantic Intermezzo,” about the Democratic National Convention of 1920, held in San Francisco (both from Heathen Days). And who can ever forget “Fire Alarm” (Newspaper Days) that captures the danger and excitement of the Great Baltimore Fire of 1904? That one event ranks with the Chicago fire of 1871 and the San Francisco Earthquake of 1906 among the great disasters of American history. Of all the city’s industries, contemporary accounts agreed that it was the press that suffered most. How Mencken and his staff overcame the challenge is a story full of strength and romance, an adventure that would bind him even tighter to the place of his birth.

AF: What do you see as the value of The Days Trilogy today? They don’t have the polemical force of his earlier work.

Rodgers: Urban centers have inspired and nourished the imagination of our greatest American writers. The Days volumes gives us a portrait of a vanished era in American history beginning in the 1880s up to the 1930s; they describe Mencken’s childhood and experiences as drama critic, newspaper reporter and columnist. They are among his most popular and celebrated works, selling only a close second to his study of The American Language. The value of this trilogy is that it provides us with context. We tend to look at the past from our own end of the telescope. But this collection is not just for the Mencken fan. I can see this LOA edition being of great interest to the general reader as well as the scholar, for all those who are interested in American studies, with its emphasis on social and intellectual history and descriptions of daily life and popular culture in the United States from the 1880s-1930s; regional and local Maryland history; American literature and language; journalism and media studies; theater; politics; for those who are interested in studying the development of voice in memoirs and autobiography or who appreciate the importance of place in American letters.

Bill Marx is the Editor-in-Chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: American history, H. L. Mencken, Happy Days, Heathen Days, Library-of-America, Marion Elizabeth Rodgers, memoir, Newspaper Days, Notes