Arts Remembrance: Farewell, Robin Williams — Manic Master of Comedy

Monday’s news of the death of Robin Williams has hit hard. His brand of irresistible joie de vivre has been indispensable for decades.

By Matt Hanson

Monday’s news of the death of Robin Williams has hit hard. Tributes have popped up all over the internet, and clips of his work are making the rounds on social media. Everyone has memories of Robin Williams, and it’s no wonder, considering he has been a pop culture mainstay since the Carter era. His comedic track record is impressively solid, too, given his versatility and the length of career – his artistic achievement outweighs his flops. This was an actor and comedian who brought out the best in each of the genres he tackled. His brand of irresistible joie de vivre has been indispensable for decades.

There’s TV’s Mork and Mindy, of course, which not only merits historical interest because it is his mainstream debut, but still works in its own peculiarly slapdash/surrealist way. Rumor has it that the show’s scriptwriters used to leave pages of the script blank — except for the words “Mork does his thing.” Whether this is evidence of genius or of needy self-indulgence is up for debate, but what’s absolutely clear is that very few actors, particularly when starting out, could possibly get away with this anarchistic license.

It’s hard to imagine what it would be like to keep up that kind of manic energy night after night onstage and then work at Williams’s breakneck pace, completing up to two movies a year. His free-associative turn as the genie in Aladdin meant that the animators had to literally redraw each of the frames to accommodate the dozens of spontaneous impressions he churned out. Good Morning Vietnam – his first Oscar nomination – offers verbal political cartooning that remains strikingly relevant, given the state of our foreign policy over the past few years: “How do we find the enemy?…Well, we walk up to someone and say ‘Are you the enemy?’ and if they say yes, we shoot them.”

It’s still fun to watch him in Terry Gilliam’s film The Fisher King as a traumatized but resolutely whimsical homeless mystic. He did Shakespeare and an Off-Broadway version of Waiting For Godot with Steve Martin (directed by Mike Nichols) in the late eighties which isn’t commercially available so far as I can tell. Someone out there must have a tape of this production that can be released. He also managed to survive Robert Altman’s infamously drug-addled shoot for Popeye, which must have been a feat in and of itself, especially since it took place during his coke addiction years. What Dreams May Come is the kind of movie I didn’t think much of when I first saw it, but I eventually came to appreciate the more I noticed what it meant to other people.

Some of his best work came from roles which required him to play against type. He excelled at portraying benevolent authority figures with a mad twinkle in their eye. The passionate Charles Keating in Dead Poet’s Society comes straight out of Liberal Fantasy 101, but nobody ever said they watched Williams for his skills at verisimilitude. Everybody should see it by the time they hit high school, and the movie doesn’t claim to any higher goal than that. He’s also memorable as the humanist doctor in the moving Awakenings, playing a fictionalized Oliver Saks alongside Robert De Niro. Despite his stints at supplying inspiration, he was never afraid to indulge in dirty or gallows humor, either. There’s a sketch (see below) from the Carol Burnett Show where he plays a rather disturbed and neurotic funeral crasher. He improvises through the entire scene and remains both funny and creepy in equal measure.

What Bostonian could possibly be allowed to forget Williams in Good Will Hunting? Yes, his regional accent was shaky at best, but somehow he perfectly fit the role. His witty but resigned former PhD Sean Maguire was, for better or worse, an Oscar turn if there ever was one. It tugged at the heartstrings, for sure, but it’s a testament to Williams’s sense of humanity that he lent every scene in that film a sense of wizened authority that makes half the movie feel like a visit to the guidance counselor you never had.

No question he also put out his share of schlock, an unavoidable fate given that his default mode as an actor was ultimately go for entertainment rather than realism or provocation. Very few people are going to run to check Netflix for, say, Toys or Jack or Man Of The Year, let alone Bicentennial Man in the next couple of weeks. It was his mawkishness that came through more than anything else when the scripts were weak and he needed a reality check. Also, he depended on improvisation when a movie desperately needed juice, and his charisma would overheat when it was overworked.

Despite the fact that people who worked with him described him as kind and generous and fun to be around, Williams openly admitted to the perennial comic’s angst about needing to be loved by the crowd. He talked to Marc Maron in a 2010 podcast about not only his love for standup but the anxieties that come with the territory. You can hear the depression in his voice as he speaks frankly about his relapse after years of sobriety and the terrible stress that comes with performing, yet he’s still funny and engaging and unfailingly decent as an interview subject who doesn‘t particularly need the exposure.

Guest starring on a recent episode of TV’s Louie, he and Louie CK meet unexpectedly at the abandoned grave of an asshole comedy promoter they both knew back in the day. After an awkwardly amusing conversation they laugh together at the absurdity of it all. It’s a brief moment though, and just before they part ways they exchange long looks and each man spontaneously promises to visit the other’s graves someday. It’s a chilling moment, given the way we now know how that particular story has ended.

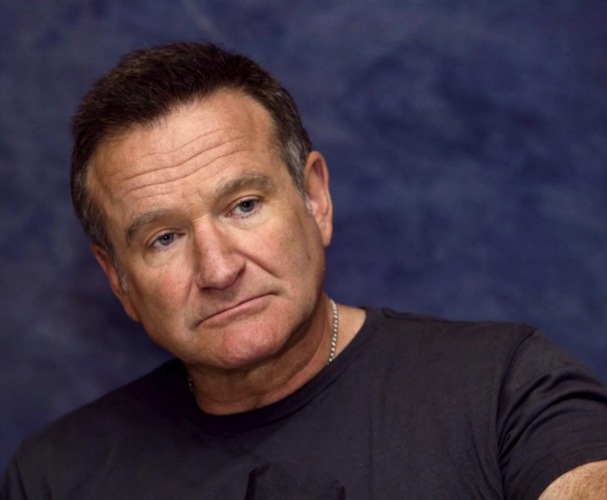

Hindsight is 20/20, but there was a sense of loneliness about Williams in the odd moments when he wasn‘t gesticulating. There was a tightness around the mouth, a bit of narrowness about the eyes. Just look at an ordinary photograph. His resting face, in between his constant impressions and jokes and loquacity, was rather stern and intensely focused. I don’t doubt for a minute that he was every bit as genuine and exuberant as he often seemed to be, I’m just amazed at the fact that he made the choice he did. The abruptness of it suggests there was even more going on in his bustling brain than he cared to share with anyone, which is especially ironic and heartbreaking considering that he’d already spent years giving far more of himself than most other performers ever muster in a lifetime.

Matt Hanson is a critic for the Arts Fuse living outside Boston. His writing has appeared in The Millions, 3QuarksDaily and Flak Magazine (RIP), where he was a staff writer. He blogs about movies and culture for LoveMoneyClothes. His poetry chapbook was published by Rhinologic Press.

This is an on target tribute-you said it all beautifully. Well done.