Book Review: “Little Failure” — Gary Shteyngart’s Memoir is Amusing But Thin

Gary Shteyngart’s memoir proffers the rhetorical zest and caustic wit of his novels, but it lacks their satiric edge.

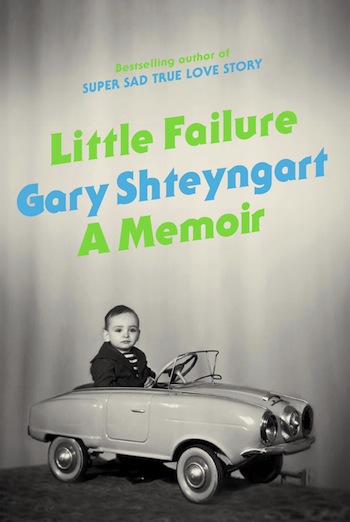

Little Failure: A Memoir, by Gary Shteyngart. Random House, 368 pages, $27.

By Matt Hanson

For most of the hip young reading public, Gary Shteyngart has consistently been one of the most popular and well-praised novelists writing today. It’s curious that at this point in his career (he’s 42), Shteyngart chose to write a memoir. He’s done rather well for himself fairly quickly – winning major awards and having his books consistently make the bestseller list. Somehow he also finds time to add a blurb to seemingly every new novel in existence. Why, then, pen the story of his life so early on and then entitle it Little Failure?

For most of the hip young reading public, Gary Shteyngart has consistently been one of the most popular and well-praised novelists writing today. It’s curious that at this point in his career (he’s 42), Shteyngart chose to write a memoir. He’s done rather well for himself fairly quickly – winning major awards and having his books consistently make the bestseller list. Somehow he also finds time to add a blurb to seemingly every new novel in existence. Why, then, pen the story of his life so early on and then entitle it Little Failure?

His last three novels already felt deeply personal, rooted in a very specific kind of experience. The warm-hearted but neurotically insecure, bookish and perpetually frazzled protagonists of The Russian Debutante’s Handbook and Absurdistan feel as if they are part and parcel of Shteyngart’s memory. The portrait of the artist in Little Failure resembles the characters we’ve met before in his fictional world. In fact, his memoir reads much more like a Buildungsroman than a conventional reminiscence.

The volume’s manic tour through the various chapters of his personal life plays to Shteyngart’s strengths as a writer, who reliably makes antic hay over his character‘s external and internal foibles. Little Failure bubbles over with engagingly intimate details. We are given a guided tour of his childhood years spent in the then-Soviet Union and then follow his family’s emigration to New York City at the aegis of his hilariously eccentric Jewish parents. There’s also an amusing account of his time as a perpetually stoned undergrad at Oberlin and his endearingly unrequited relationships with women. We are given the lowdown on our hero’s geographical and emotional hopscotch up to the point when he got his first break as a writer and debuted with the entertaining breakout success The Russian Debutante’s Handbook back in 2002.

Evelyn Waugh once said that when a writer is born into a family, that family is doomed. One of the perennial interests of a memoir, especially that of a writer, is to find out what kind of treatment the family members are going to get. Our loveable little failurchka was born in what’s now called St Petersburg (or, as he calls it, “St. Leningrad” or “St. Leninsburg”) in 1972 to parents who seemingly come straight out of Neurotic Scribbler 101. Even as a successful novelist, Gary is perpetually badgered at the dinner table with comments about how they heard on the internet that his books won’t last, that they aren’t selling, and that he needs to find a nice Jewish girl and give up this writing business and just go to law school already.

Add to this skeptical advice the admonition that, whatever he does, “don’t write like a self-hating Jew.” The eccentric, demanding parent scenario is a rather old trope at this point, especially after the recent here’s-my-horrific-childhood memoir trend. Frankly, once you read about the author’s years of daily therapy and occasional panic attacks, you start to wonder if his parents could really have expected him to write about anything else.

So it comes across as particularly poignant, not merely self-deprecating, when Shteyngart breaks the fourth wall to talk about the meaning of writing in his life: “I write because there is nothing as joyful as writing, even when the writing is twisted and full of hate, the self-hate that makes writing not only possible but necessary. I hate myself, I hate the people around me, but what I crave is the fulfillment of some ideal.” There’s something very appealing about an American writer who dares to come clean, valuing a voice that is not propelled by sweetness and light. At his best, Shteyngart is a parodist whose endearing humor neatly balances mangy bitterness and blithe wit. Given his dour inspiration, narcissistic self-obsession would be an easy out. Shteyngart’s honesty and knowing irony makes this statement into an ars poetica rather than a glib expression of Swiftian self-admiration.

Shteyngart’s Russianness is treated with the author’s trademark blend of whimsy and acid. It’s amusing to read that his grandmother paid the twelve-year old author a slice of cheese per page to write a fantastical novel about Lenin and a magical golden goose. His family was nothing if not mercenary: his mother charged him for each of the butter-stuffed chicken Kievs she cooked for him. Shteyngart spent many anguished evenings as an alienated and guilt-ridden young Republican, hired to do paranoid telephone fundraising for George Bush Sr‘s 1988 Presidential campaign (“You just can’t trust the Soviets, ma’m! Look at Breznev!”). Shteyngart doesn’t moralize about or write off his pre-Glasnost roots; neither does he sentimentalize them. It makes perfect sense that the writer, moving from one charged political space to another, would eventually make his name as a social satirist.

In his memoir, Gary Shteyngart doesn’t moralize or blithely write off his pre-Glasnost roots. He does not sentimentalize them either.

A sharp perception of the socially absurd propels the best episodes in Shteyngart’s novels. Little Failure comes off as a fast paced and enjoyable story, but overall it simply doesn’t pack the incisively sardonic power of his best fiction, Absurdistan especially. The latter’s anti-hero — the 325-pound Misha Vainberg, son of the 1,238th richest man in Russia, clumsily stumbling through the moronic infernos of Russia and America — was so compelling because, for once, the promise of take-no-prisoners international satire was fulfilled. Shteyngart’s vision of the mad world around us can be wickedly acute; even more admirably, he has the nerve to affront the reader. No one is safe from his barbs, including himself.

Alas, Shteyngart has not always been up to the ace lampooner’s task. Absurdistan hit its social and geopolitical marks and then some, while Super Sad True Love Story lamely stuck to much easier and safer subjects for parody, from Facebook to Juicy Couture. It’s like a once-edgy standup comic who decided to resort to nothing but jokes about George W Bush being dumb. It was not only disappointing to see Shteyngart lose his edge, it was also a bit worrying, given his previous potential.

Still, Little Failure has the rhetorical zest and caustic wit of the novels, which makes it worthwhile in and of itself. But the volume also raises the question of whether the author might be killing time until he finds inspiration again. Could exhaustion have set in? Now that his readers have gotten a taste of the real Shteyngart, it is clear that he sounds a lot like a character in one of his novels. It will be interesting to see where he goes next in his fiction because, as the saying goes, you can’t go home again.

Matt Hanson is a critic for the Arts Fuse living outside Boston. His writing has appeared in The Millions, 3QuarksDaily and Flak Magazine (RIP), where he was a staff writer. He blogs about movies and culture for LoveMoneyClothes. His poetry chapbook was published by Rhinologic Press.