Visual Arts: Going Beyond the Skin

This MFA exhibition displays some of the most intricate manifestations of tattoos in woodblock prints, leaving the viewer curious about its footprints in contemporary art and popular culture.

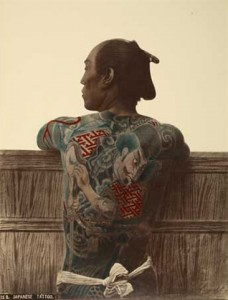

Photograph of a tattooed man by Kusakabe Kimbei

By Yumi Araki

Under the Skin: Tattoos in Japanese Prints is showing at the Museum of Fine Arts through January 2, 2011.

As a cultural prelude to a business trip I’m taking to my home country of Japan, I decided to visit an art exhibition whose subway ad beckoned me with a familiar image of a fully tattooed Japanese warrior.

Showing since April at the Museum of Fine Arts, “Under the Skin: Tattoos in Japanese Prints” explores the meaning and influence of tattoos in Japanese woodblock prints. It’s also a rare collection of postcards, manuscripts, and books by artists from the Edo period (1615-1868) that has only recently been made for online and public display.

While each piece illuminates the culture and context in which they were created, the exhibition left me wondering how these prints have influenced contemporary iconography and how they became blueprints for other art forms. Where do we see the influences of this art?

Aside from coasters and mugs found in a Japanese gift shop, many traditional art forms emulate prominent printer Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s (1797-1861) woodblock aesthetic. About a third of the exhibition pieces don Kuniyoshi’s name, and his artistic influence can be recognized in the heroically posed subjects and the iconic creatures and floral patterns printed intricately across their flesh. As the son of a printmaker, Kuniyoshi’s pieces incorporate meticulously detailed designs, which remain a signature characteristic of Japanese art.

Kuniyoshi’s playbill-like prints featuring thespians from Edo, Japan’s then capital, are evocative of the magnificently expressive actors from kabuki, a traditional Japanese theatre art. In fact, around the same time Kuniyoshi’s prints became popular in Edo, bodysuits simulating tattoos became part of a kabuki actor’s costume as a means to quickly identify the character for the audience. Benten Kozō Kikunosuke, the lead figure in Kawatake Mokuami’s play chronicling the tales of five thieves, disguises himself as a woman and, at the drama’s climax, reveals his tattoos to prove that he is a man.

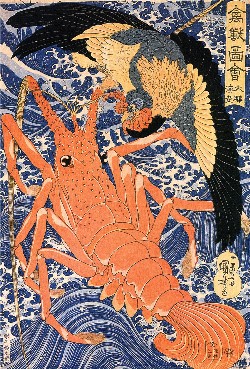

Kuniyoshi Utagawa’s Lobster

It makes sense that Kuniyoshi’s tattoo print collection found its way into theatre because its origins lie in dramatic literature. Kuniyoshi studied under Katsushita Hokusai, one of the most celebrated Japanese artists and the woodblock printer who produced the iconic tidal wave print. Katsushita was also an expert on Chinese painting, which drew his disciple, Kuniyoshi, to the country’s martial arts fiction.

He was particularly drawn to the heroic folklore in Outlaws of the Marsh (Shui Hu Zuan in Chinese, or Suikoden in Japanese). He crafted a woodblock print collection featuring the 108 outlandish heroes in the volume, which chronicles the journey of 108 bandits, all determined to embrace their flaws and integrity as unconventional heroes. While few characters in the book have tattoos, Kuniyoshi nevertheless decorated each in his prints with magnificently detailed skin art.

Each character’s energetic valor must have inspired Kuniyoshi, reflected in action-packed images such as “Yan Qing, the Graceful (Roshi Ensei, cir. 1827-30).” Intricately carved, indigo tattoos of lions and peonies highlight martial warrior’s Yan Qing’s battle to fend off enemies atop a stone-tiled roof.

The warriors in Outlaws of the Marsh weren’t “heroes” in the traditional sense; each possesses a dark side or a flaw that might render him a villain in moralized Mother Goose folklore. But Kuniyoshi reveres them nevertheless. “The Tattooed Priest Lu Zhishen (Kaosho Rochishin, cir. 1843-47)” depicts an elderly, bald man with indigo tattoos covering his entire body.

According to legend, Lu Zhishen hid in a Buddhist monastery to escape persecution after killing a man in a duel but eventually succumbed to outlandish tendencies, which gave away his hiding spot. To illustrate the tattooed priest’s verve, Kuniyoshi embellishes his skin with perfectly shaped sakura, or cherry blossom petals. By using a Japanese symbol of celebration or a new beginning, Kuniyoshi celebrates Lu Zhishen’s perseverance through his tattoos.

This presentation of outlandish heroism must have appealed to Japanese mobsters who, during this era, embraced tattoos of elaborate creatures and designs as a means to mask the more unsightly marks that identified their membership in a criminal gang. Symbols of brotherhood and honor are infamous inky signs of the yakuza, whether it be a magnificently “carved” (as it is called in mobster lexicon) pair of sleeves or a full tattoo bodysuit.

In particular, “Konjin Chogoro, from the series Sagas of Beauty and Bravery” (Biyu Suikoden, cir. 1839-1892)” by Kuniyoshi’s only pupil, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, exemplifies the yakuza tattoo aesthetic—bold patterns and aggressive depictions of fang-showing animals as representations of the yakuza spirit.

Creator:Utagawa Kuniyoshi. Title: Tammeijiro Genshogo, from Tsuzoku Suikoden Goketsu Hyakuhachinin no Hitori. (Credit: Brooklyn Museum)

Tattooing became rampant in the underworld during the Meiji Restoration when oligarchs attempted to modernize Japan by banning anything deemed “un-Western.” Available in underground parlors, tattooing soon became a popular activity for criminals. The legacy of Kuniyoshi’s creatures and patterns lived on engraved on the bodies of yakuza. This type of tattoo is still considered taboo in Japanese society.

This art form continues to thrive in a number of different ways, but the exhibition clearly highlights our timeless connection to tattoos as an art of commemoration and reverence. The expression on the male figure in Kitagawa Utamaro I’s “Onitsutaya Azamino and Gontaro, a Man of the World (Onitsutaya Azamino, isami-tsu Gontaro, cir. 1798-99)” makes this elemental value clear: tattooing signifies an act of love, a physical manifestation of one’s devotion to another. In the print the man grimaces as his lover carves her name into his right bicep.

Perhaps what’s most impressive about this exhibition isn’t mentioned in the exhibition descriptions—woodblock prints are incredibly laborious masterpieces created by printing each particular color one at a time. While the prints are shaded with muted hues, most prints feature a hero draped in a magnificently color robe with highly intricate tattoos covering the rest of his or her body. Admiring the meticulous craft required to depict intricate sleeves and full-bodied tattoos on dramatically posed subjects is just one of the unexpected rewards proffered by “Under the Skin.”

Tagged: Boston, Japan, Museum of Fine Arts, Tattoos, Under the Skin, Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Visual Arts, woodblock

I, like you, much enjoyed this show. The colors and forms are exquisite.

It all came to an end, as per the show, in that last print,

illustrating the russo-japanese war. Bye bye mythology. Hello

modernity.

My question, I think like yours, is where this powerful visual impulse

went in contemporary Japan.

I allow myself to surmise the answer is not hard to come by: it went

into manga and anime—powerful, influential, visual media.