Classical CD Reviews: Jon Nakamatsu plays Schumann, Bach’s “Brandenburg Concertos,” and Mendelssohn’s “Lobgesang” (Harmonia Mundi)

A round-up of classical music CD releases from Harmonia Mundi: Jon Nakamatsu’s uneven interpretation of Robert Schumann piano pieces, Freiburger Barockorchester’s ingratiating performance of the Brandenburg Concertos, and a notable new recording of Mendelssohn’s Second Symphony.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

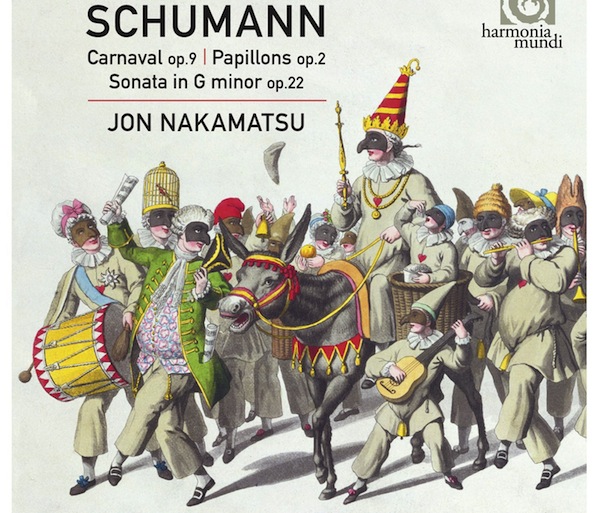

Few composers articulated the extremes of musical Romanticism more enthusiastically or brilliantly than Robert Schumann. And pianist Jon Nakamatsu’s new album on HM showcases three of Schumann’s most extraordinary solo keyboard contributions: Papillons, Carnaval, and the Piano Sonata no. 2. Each piece filled with technical demands, to be sure, but also uniquely affecting expressive powers that offer a special kind of challenge for performers.

On this disc, Nakamatsu achieves these last most convincingly in the sonata. Schumann wrote the piece between 1833 and 1838. It’s filled with tempestuous, driving energy that, much in the spirit of the times, expresses some deeply personal emotions: Schumann’s wife, Clara, described the work, observing to her husband that “your whole being is so clearly expressed in it.”

In this performance, Nakamatsu seemingly inhabits the volatile inner personality of Schumann, throwing himself into the piece with abandon, hurtling through the restless outer movements without once looking back and delivering a nicely balanced, reflective account of the luminous slow movement. Despite the overall intensity of his playing, he also manages an impressive amount of tonal variety and articulation throughout, even if the first movement comes off a bit too breathlessly at times.

Unfortunately, the other two works on his program, Papillons and Carnaval, while having some beautiful moments between them, lack the overall impetuous conviction of the sonata, demonstrating a general stiffness of character and interpretive literal-mindedness. Just listen to Nakamatsu’s “Eusebius” from Carnaval – a musical realization of Schumann’s dreamy, introspective self – and compare it to Uchida’s or Barenboim’s. A movement that should float free of time and space here, by contrast, sounds grounded in both.

And so it goes, with a surprisingly passion-less “Chiarina” and a matter-of-fact “Papillons.” Technically, the playing is solid in both of these pieces, but, for interpretations, you can do better elsewhere.

*****

Consistently brilliant on their new recording of the complete Brandenburg Concertos is the Freiburger Barockorchester, who play with not only a deep understanding of the music but also palpable exuberance. This is clear from the downbeat of the first concerto, with its braying horns and oboes leading the way in a reading that captures the celebratory nature of this work, especially in its moments of rhythmic dissonance.

The remaining five concertos are etched with a similar mix of enthusiasm and musical insight. There’s remarkable clarity in the contrapuntal interactions between the soloists in the famously virtuosic Concerto no. 2 and an appealing blend of opacity and jauntiness in the Sixth. For my money, though, the most notable performance belongs to the Concerto no. 4, for two flutes and violin, which comes across with a sense of gracious restraint that feels utterly natural.

In all six pieces, the Freiburger’s playing is clean, tonally secure, and deeply engaged – especially among other, with gamely dialogues that respond to all the music’s twists and turns. In a word, it’s wholly ingratiating: there’s no shortage of recordings of this repertoire with period ensembles, but for a recent addition to the canon you’re not going to do much better than this.

*****

Of his five symphonies, Mendelssohn’s Second, subtitled Lobgesang (“Hymn of Praise”), is both the strangest and the most brilliant. Written to commemorate the 400th birthday of the printing press (in 1840), it combines elements of the symphonic tradition handed down by Beethoven with those of the oratorios and cantatas of Bach and Handel: three instrumental movements capped off by a lengthy section for chorus and soloists. It’s a fascinating hybrid composition that turns up rarely on concert programs and, just about as seldom, on disc. So Pablo Heras-Casado’s new recording of the work with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and Chorus is both notable and welcome.

Heras-Casado’s performance begins with an energetic opening movement, one that’s also filled with nuance (listen to the string swells in response to the opening trombone melody), and it’s a sign of things to come: taut, lean playing, certainly, but highly expressive all the same.

The Lobgesang’s payoff comes with the choral/vocal section that begins with the rich (and dramatic) accompaniment of orchestra and organ. In each of their appearances, the Chorus of the Bavarian Radio delivers crystalline diction – Mendelssohn’s writing in the Lobgesang owes as much to the polyphony of Bach as it does anywhere in Elijah or Paulus – and all the words come across vividly.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Brandenburg Concertos, Carnaval, Freiburger Barockorchester, Harmonia Mundi, Jon Nakamatsu, Lobgesang, Mendelssohn, Pablo Heras-Casado, Papillons