Book Review: Philippe Jaccottet’s “Seedtime” — Exploring the Inherent Mysteries of the World As It Is

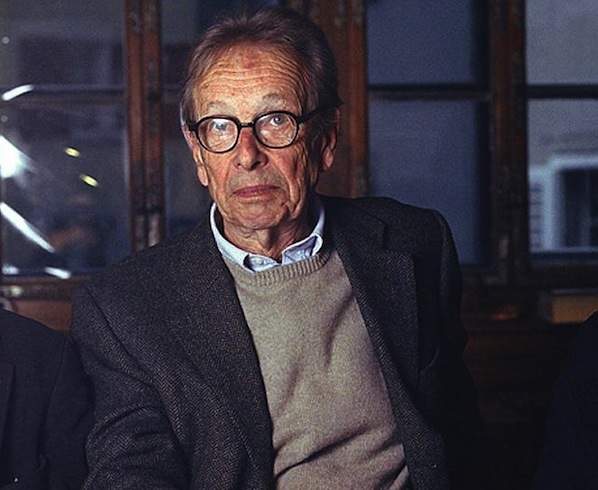

French writer Philippe Jaccottet’s ever-questioning poetic analyses of haunting ephemeral perceptions are carried on with such scruple and sincerity that, for his European peers, he has become the model of literary integrity.

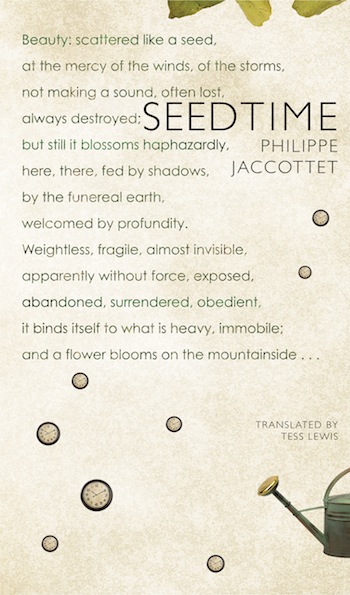

Seedtime: Notebooks 1954-1979 by Philippe Jaccottet, translated from the French by Tess Lewis, Seagull, 345 pp. $21.

Oeuvres by Philippe Jaccottet, edited by José-Flore Tappy, Gallimard (“Pléiade” edition), 1626 pp., 66.50€.

By John Taylor

Born in Switzerland in 1925 and a longtime resident of France, Philippe Jaccottet writes poetry and poetic prose that are noted for the fragility and fleetingness of what he seeks to pinpoint. Through subtle, at once deft and circumspective evocations of natural objects or phenomena, he attempts to define instants when he has had the impression of glimpsing something—but was it really an objective “thing” or merely a mirage?—lying just beyond the threshold of appearances. Time and again he must ultimately acknowledge the absolute factuality of what he has seen or sensed, but his quest continues. Jaccottet’s ever-questioning poetic analyses of haunting ephemeral perceptions are carried on with such scruple and sincerity that, for his European peers, he has become the model of literary integrity.

Tess Lewis’s fine translation of La Semaison (1984) as Seedtime, a significant book in Jaccottet’s oeuvre, appears almost at the same time as the superb Gallimard-Pléiade volume of the poet’s collected works, as edited by the poet and scholar José-Flore Tappy. Needless to say, it is a rare honor for a living writer to be published in the Pléiade, the French equivalent of the Library of America series. Other exceptions from the past four decades include René Char, Julien Gracq, and Nathalie Sarraute. Whereas some Pléiade editions have been marked by excessive annotation, this volume reveals a perfect balance between readability and meticulous editorial scholarship.

Seedtime gathers Jaccottet’s notebooks from the years 1954-1979. They constitute both a logbook and a laboratory. Seedtime is a logbook in the sense that the poet jots down his reflections and, even more often, what he has observed usually in and around Grignan, the small Provençal town in which he settled in 1953, about six months before writing down this first “note” of Seedtime:

Attachment to the self renders life more opaque. One moment of complete forgetting and all the screens, one behind the other, become transparent so that you can perceive clarity to its very depths, as far as the eye can see; and at the same time everything becomes weightless. Thus does the soul truly become a bird.

This initial remark already defines the fundamental intuition that has guided Jaccottet ever since: the necessity of getting beyond self-attachment if one is to dismantle comforting illusions and to penetrate ontological enigmas such as those mentioned above. As for other French poets (Yves Bonnefoy and Pierre-Albert Jourdan come to mind) who take on this same challenge, a paradox is involved. Writing implies the participation of the self, even as sense impressions imply the existence of the subject who receives them. It is a contradiction in terms to imagine that one can “de-self” perceptions (and the very act of imagining that one can de-self them also, of course, implies the existence of the imaginer). All the while retaining a light touch in his verse and a stylistically more pensive one in his poetic prose, Jaccottet delves deeply into this paradox, which qualifies our experience of being; that is, our yearning as well as our uncertainty. It could be said that the poet attempts to get beyond both and see—“be”—more clearly. His second entry in Seedtime is a characteristic on-the-spot perception that de-emphasizes the self and attempts to capture the inherent mysteries of the world as it is:

Snow covers the fine grass. It whirls as it falls like the seeds of maples and settles like a single vast and silent seed onto the village.

Or the sliver of moon above black twigs.

As to the “laboratory” aspect of Seedtime, the poet not only records significant perceptions such as the preceding one, but also sometimes drafts strophes that will eventually either be crafted into poems or simply remain in the notebook as fragmentary versified sketches. During the years covered in this first volume of Seedtime, Jaccottet published the collections L’Ignorant (The Ignoramus, 1958), Airs (Airs, 1967), Leçons (Lessons, 1969), Chants d’en bas (Songs from Below, 1974), and À la lumière d’hiver (In Winter Light, 1977), as well as his first volumes of poetic prose, Paysages avec figures absentes (Landscapes with Absent Figures, 1970) and À travers un verger (Through an Orchard, 1975). Readers of these volumes will detect echoes and spot specific common concerns in Seedtime. Moreover, one perceives the origins of Jaccottet’s increasing use of poetic prose, a genre that becomes predominant in his work beginning in the 1990s.

This question of verse vs. prose is no matter of whim or formal ambidexterity. In a passage of Seedtime dated September 1965, Jaccottet writes down a sentence—“I do not want to cheat”—that has ever since remained intimately associated with his poetics. Here is the context:

What makes expressing myself difficult today is that I do not want to cheat—and it seems to me that most people cheat, more or less, with their own experiences. They put it in parentheses, cover it up. At that point certain words should enter into poetry, words that it has always avoided, been wary of, and yet without moving towards naturalism, which, in its own way, is also a lie. There is an area between Samuel Beckett and Saint-John Perse at opposite extremes, each systematic in his own way. But then one is always just inches from the impossible.

The poet focuses here on the question of rendering experience faithfully. But the issue of stylistic honesty and scrupulous truth-seeking increasingly applies, as the decades go by, to his skepticism about poetic “beauty” and thus about the illusive affects of verse forms. Indeed, Jaccottet implicitly asks ever more often: what if formal stylistic beauty constitutes just another mirage? In Seedtime, in May 1971, he comes to the conclusion that “the better you understand how [poetry] should be done, the less you are able to write it. Virtuosity comes with the void.” Five years earlier, in May 1966, he notices the shadow of a tree on flowers in bloom and reacts: “I now have that shadow of pain behind me no matter what I write. It makes all the poems I’ve written seem too fluid and almost every sentence as well. Because no word is pain; on the contrary, it is detached, intact.”

This kind of self-critical retrospection recurs often. Jaccottet asserts that the poet must constantly question even those qualities—stylistic fluidity, in this case—that are normally held up as universal goals for writers. To cite the preceding example, he intends to go after that “pain,” whatever the literary costs. This is one of the profound lessons of Seedtime.

Furthermore, as a poet desirous of “air” and “space,” he is suspicious of closed literary perspectives—of “closure” in any of its manifestations. In a remark made as early as March 1960, he posits that “beauty is born when the finite and the infinite become visible at the same time, that is to say, when we see forms but recognize that they do not express everything, that they do not stand only for themselves, that they leave room for the intangible.” Two years later, he formulates a sort of poetic credo that likewise examines the issue of “beauty,” of finding the “right weight” for words and, if necessary, of writing “against oneself”:

Beauty: lost like a seed, at the mercy of the winds, the storms, not making a sound, often lost, always destroyed; but still it blossoms haphazardly, here, there, fed by shadows, by the funereal earth, welcomed by profundity. Weightless, fragile, almost invisible, apparently without force, exposed, abandoned, surrendered, obedient—it binds itself to what is heavy, immobile; and a flower blooms on the mountainside. [. . .] And so, therefore, one must go on scattering, risking words, lending them exactly the right weight, not giving up until the end—against, always against oneself and the world, until one manages to overcome all opposition through the words themselves—words that transcend boundaries, barriers, that break through, cross over, open and finally triumph, occasionally, in fragrance, in colour—for an instant, only an instant. That, at least, is what I cling to, uttering what is almost nothing. . .

Seedtime is thus an important work in that Jaccottet already tries out the relative “honesty” of certain kinds of writing. As to prose, he usually employs the most spontaneous forms: the note, the short description, the diary entry, the literary or philosophical reflection. In October 1959, he ponders the overall presentation and atmosphere of literary works, even in two poets, Giacomo Leopardi and Friedrich Hölderlin, whose quests resemble his own in certain respects:

Reservations (absurd, of course!) with regard to Leopardi’s allegories and thought, tension in Hölderlin, Baudelaire’s posing.

Perhaps it is time to try something else, in which lightness and gravity, reality and mystery, detail and space enter into a harmony that is not quiescent but alive. Grass, air. Infinitely fragile and beautiful glimpses—as of a flower, a jewel, gold work—placed in the extraordinary immensity. Stars and night. A vast and fluid discourse, airy, in which jewels of language are discreetly placed. Just as something reappears now and again in the mist. Or else, the way you suddenly remember the depths of space and time while busy with some menial task.

All of Jaccottet’s future themes are present in Seedtime. The book reveals, for instance, how grappling with death nonetheless induces him to give a life-affirming orientation to his writing. Jaccottet can be bleak because, once again, he “doesn’t want to cheat” by diminishing death through literary rhetoric, which can also mean over-emphasizing man’s finitude; yet he refuses to relinquish all hope, even if, by “hope,” no transcendence is implied but rather only an attempt to live more truly—to accept Being as it is. In a deep sense, much of Jaccottet’s writing is about “how to live.” As early as November 1959, he juxtaposes “decay” and “praise”:

That which grips us as it consumes itself, disappears.

Burning wood. In me, through my lips, only death

has spoken. All poetry is the voice given to death.

May our decay praise, celebrate. May our defeat

shine, resound.

If I were not approaching the end, I would not see.

Birds circling or shooting like arrows across the sky, no

one sees you but the dying, those who are being

worn down, who are slowly turning to dust.

Such lines can be kept in mind when one is reading his later book-length poem Leçons, available in Mark Treharne’s version as Learning. . . (Delos Press, 2001). Inspired by his father-in-law’s death in June 1966, Leçons, which was published three years later, probably takes root in these lines, recorded in Seedtime that same month:

In this year when the crown of white roses

Reminded me of sparse, unkempt hair

On the brow of an old man resigned to his suffering with sad courage

[. . .]

If we could have a fraction of such wisdom and courage

Rather then too much useless knowledge and too many dreams.

[. . .]

Now that I have seen death, it fascinates me less than before I knew it.

I’d like to turn away from it as from something incomplete and, perhaps, meaningless.

It seems to me that the light has grown today

Like a plant.

This is the first volume of Seedtime. Awaiting translation are the two subsequent volumes, La Seconde Semaison: Carnets 1980-1984 (1996) and La Semaison, III: Carnets 1995-1998 (2003), as well as two similar collections of “notes” that were not included in the three installments of the Seedtime series: Observations et autres notes anciennes 1947-1962 (1998) and Taches de soleil, ou d’ombre: notes sauvegardées 1952-2005 (2013). Needless to say, we need these books in English, too.

John Taylor is also a translator of Philippe Jaccottet (And, Nonetheless: Selected Prose and Poetry 1990-2009, Chelsea Editions, 2011). His version of Jaccottet’s Truinas, an evocation of the death of the poet André du Bouchet, is forthcoming from The Delos Press. Taylor’s most recent personal book is If Night is Falling (Bitter Oleander Press, 2012).

Tagged: Contemporary French poetry, French prose, Philippe Jaccottet, Seagull Books, Seedtime, Tess Lewis