Short Fuse: Xiangqi Fever

By Harvey Blume

To play Xiangqi (Chinese chess) as earnestly as I have been lately is to revisit a familiar situation, one in which I am at the gateway of another culture, hungry for the experience, but positioned as a junior. That was the case with African drumming and with neurological difference, for example, especially Asperger’s Syndrome. I studied and wrote about both (a book pertaining to the former, many pieces about the latter) but could never be full-fledged.

Is it absurd to stake out such positions? Is it a sign of open-mindedness, or of failure and flight from one’s own cultural possibilities?

(But wait, I forgot! This peculiar sort of intervention, of sympathetic nosiness, has another name — anthropology!)

I wanted to play Xiangqi today in Harvard Square, and was cruising for opponents. I found a young Chinese guy playing Go, who said he played Xiangqi, too. He was surprised, as Asians often are, to see a Xiangqi board in Holyoke Center, well-known for western chess, but mine was set up, and we played.

We played to the quiet but mounting amusement of an older, nattily dressed, dark-skinned Chinese man who had next to no English. It took a while for this gent to break his silence. When he did, I had to coax the kid into translation. I suspect the Taiwanese-born kid of initially, for reasons that will forever be obscure to me, pretending not to know that the wash of sounds coming toward him were his first language, Chinese.

The older guy’s observations were hilarious, probably all the more so in the original. He explained, in great detail, that the kid’s game was hopeless, and that I shouldn’t entertain any illusions that mine was better. The fellow smiled politely at me as he uttered damnations in Mandarin that the kid whooped at and I found uproariously apropos.

I invited him to play.

I suggested he first play the kid, while I grabbed some food. With a bow, the gentleman acknowledged my deferring to him. After the kid, he played me.

The results in both cases were entirely predictable.

He gave me a two move opening handicap. I had received a more astonishing — insulting? — four move handicap in Chinatown, once the players there noticed I kept coming back, perhaps the only non-Asian to do so on somewhat consistent basis, and had to be assigned my place in the Xiangqi order by being properly demolished. The guy who did the deed folded his hands over his tummy and smiled, lackadaisically, at his Xiangqi cohorts, as he smoothed my way toward checkmate. Every now and then, I noted with some pride, he dislodged hands from tummy and craned his neck to study the board a bit. I took that to mean that I had for one move made him think.

I might have done a little better with my two move handicap today had it not been late afternoon. I needed a snooze more than an extra move. Nevertheless, I sped the game on, which is more than I was able to do last summer, when I was just learning and the ideograms would now and then crumble into unintelligibility. The horse would look like the cannon, the elephant would look like the horse and all of them looked like scorpions. In short, my game fell apart. Chinese chess was just Chinatown to me, Jack.

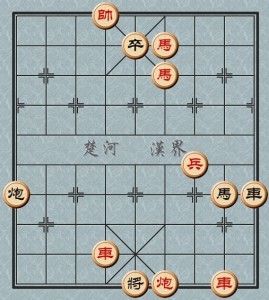

![]() My Xiangqi collapsed especially hard when I played a Vietnamese veteran of the game. (China and Vietnam play the same chess whereas Korea and Japan enjoy their own variants, the Japanese version — Shogi — being, according to some, at the outer reaches of human game comprehension.). This Vietnamese guy was about the same age as today’s elder, but not so genteel. Shaking his head in disapproval, he said of me: “Play like a baby”. For him, my collapse was a sign, if not of true idiocy then of contempt for the game.

My Xiangqi collapsed especially hard when I played a Vietnamese veteran of the game. (China and Vietnam play the same chess whereas Korea and Japan enjoy their own variants, the Japanese version — Shogi — being, according to some, at the outer reaches of human game comprehension.). This Vietnamese guy was about the same age as today’s elder, but not so genteel. Shaking his head in disapproval, he said of me: “Play like a baby”. For him, my collapse was a sign, if not of true idiocy then of contempt for the game.

A year later, this Vietnamese still frequents Harvard Sq., where he’s devoted to western chess, or rather its high speed spin-off, blitz. Last I saw him, he muttered “checkmate” derisively as he passed. I’d like to challenge him to a rematch. But I still hear him saying, as if to a tot: “I don’t play Xiangqi with you.”

(A high tolerance for humiliation may be the entrance fee to another culture.)

I’ve improved since then. Today, against the Chinese gent, I merely lost. Knowing how to lose is not as good as knowing how to win, of course, but it beats mental paralysis.

And I beat the kid, who grew up with the game but hadn’t played in a while. He’s a perfect sort of opponent for me. Some aspects of the game are native to him that still give me grief. This pertains to horse moves especially: The horse of Xiangqi becomes, in the medieval nomenclature of western chess, that fine feudal fellow, the knight. Horse and knight move in identical ells. But the horse lacks that other unique talent of the knight — the ability to jump. The horse can be blocked, — jammed, hobbled — and often is. The jamming and unjamming of pieces in Xiangqi is, for me, the special rhythm of the game, a kung fu kind of rhythm: Block turns to blow turns to block turns to blow. . . .

Today, I saw some things on the board this Taiwanese kid didn’t. But he had the advantage of thousands of games played as a boy. He took lots of time between moves, as if trying to bring his childhood Xiangqi back.

I wonder who the old guy is. He does not go to Chinatown to play, he said, and I’ve never before or since seen him in the Square. He refused to take my place on the stone chair opposite the chess table. I tried to insist he take this pride of place when he played, but he declined, explaining through the kid that stone chairs ruin pants. As noted, he was nattily attired. What was he up to wandering around the square in his nice duds, this slim elderly dude with a cool smile and a terrific tan? I’d like to have a few more elements of his story.

But let’s leave anthropology aside for the moment. There’s another point I want to make about the allure of Chinese chess.

I may be approaching it with some of the same unbridled, defenseless fascination I felt for chess when I first deciphered it at age seven. It occurs to me that it is in order to rekindle that boyhood sense of game wonder that I’m willing to take my lumps at Xiangqi.

Besides, the pieces — discs with bright red, green or blue ideograms — exude a sort of glamour and sense. They are like knobs on a cosmic console that need only to be touched to buzz, flicker and power up. They look juicy with significance

But sometimes, after I’ve sat down and played perhaps the billionth game of Xiangqi ever — there are a lot of Chinese people and they have been playing amongst themselves for fifteen centuries — the pieces lose their luster. The spell is broken. All I feel is older.

Chess, no matter what the outcome of a game, never left me with just that feeling at age seven, I don’t think.

[…] Harvey Blume spielt Xiangqi und hat seine Schwierigkeiten damit. Kommentieren […]